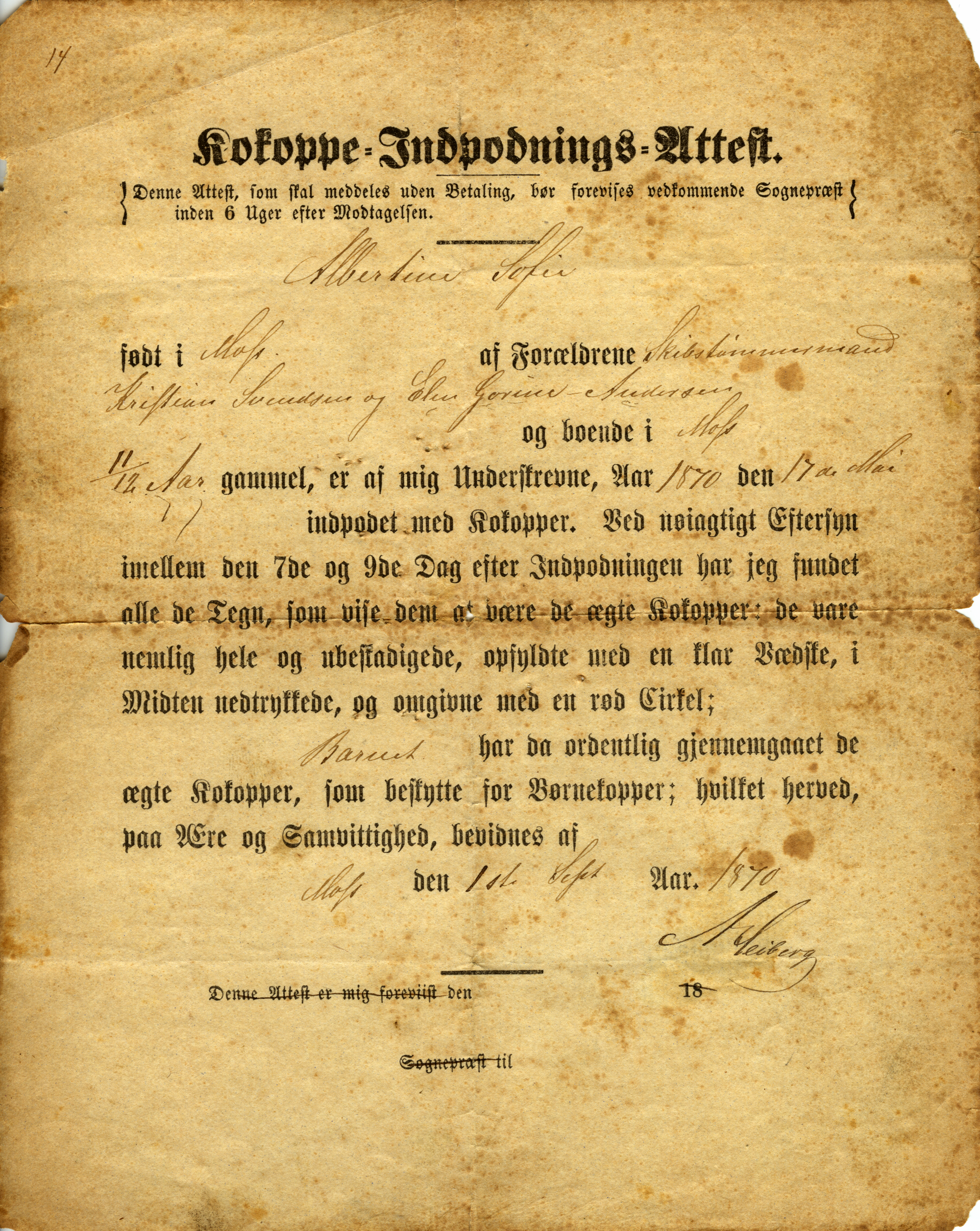

certainly qualified — a certificate of vaccination from 1870 for Albertine Sofie, daughter of August Kristian Svendsen and Elen Thorine Andersdatter. Not easily decipherable, but easily able to engage my imagination.

certainly qualified — a certificate of vaccination from 1870 for Albertine Sofie, daughter of August Kristian Svendsen and Elen Thorine Andersdatter. Not easily decipherable, but easily able to engage my imagination.

or The Family Tree That Wasn’t

Flashback: A city clerk’s office, Norway, mid 1990ies. Me, wanting to change the last name I inherited from my dad (Holmboe) to the one I didn’t inherit from my mum (Jenssen). The clerk, explaining that according to law this is not possible ’cause the former is so well protected you can’t even get rid of it. You can’t get it, either, only be born or married to it. Bummer, dude.

Flashback: A, much overdue, throwing–out–old–crap session. My husband and I were going through old papers, and came across one that  certainly qualified — a certificate of vaccination from 1870 for Albertine Sofie, daughter of August Kristian Svendsen and Elen Thorine Andersdatter. Not easily decipherable, but easily able to engage my imagination.

certainly qualified — a certificate of vaccination from 1870 for Albertine Sofie, daughter of August Kristian Svendsen and Elen Thorine Andersdatter. Not easily decipherable, but easily able to engage my imagination.

We kept that one.

If “tl;dr” to you means “anything longer than the footy betting pool coupon”, stop reading. This’ll be substantially longer than that.

In the following I use the symbol “b.” (for “born”), “d.” (for “died”), “♂” (for male), and “♀” (for female). Yes, that’s very binary, but in this context it is what it is.

The reason is due to the, faint perhaps, assumption that this might be read by non–Norwegians. Our names are not necessarily easy to gender–classify for others, and in an article on genealogy who birthed whom gets a little bit important. All very complicated.

Moss, a coastal city in the south–eastern part of Norway, is where I grew up. It remains a small city of perhaps twenty thousand, once so proud of its iron works, glass factory, shipyard, and paper factory – the latter which gave the place that distinct malodorous atmosphere which made it a household name throughout the country.

We — that is that branch of the family that reached its zenith with me :) — are for the most part from Jeløya, an peninsula–turned–island separated from the city by a canal since 1855; it is at Jeløya we find the shipyard which, later on, plays an important part in our story – and in the world: that yard produced the very first of the Moss LNG Carrier type of liquid gas tankers in 1973.

It is also where mum grew up and lived until she moved to Oslo and met my dad. More on that later.

Today Moss is a vastly difference place. The heavy industries are all gone; a good thing for the atmosphere, but less so for the culture and the city as a whole. A “mere” 45 minutes from Oslo by train, the locals are outnumbered by the commuters, the price of homes has gone through the roof, and the traffic is — pardon my French — a bloody mess.

The Jenssen family has been a fixture in Moss for many years, but can be somewhat difficult to track down. To a large extent this is due to the curious Nordic way of using patronymics — the practice where a child’s surname is composed from the father’s given name with a “son” (“sen” in Norwegian and Danish, “son” in Swedish) or “daughter” (“datter” in Norwegian and Danish, “dotter” in Swedish, “dóttir” in Icelandic and old Norse) suffix.

The entirely imaginary Olav Jenssen would, thus, be “Olav, son of Jens”; Olav’s son “Trygve, son of Olav” would be Trygve Olavsen. What we to–day call a surname changed every generation, making it rather hard to determine who was in which family. There are a number of families “Jenssen” in Norway, although few use the double–s; even fewer are actually related.

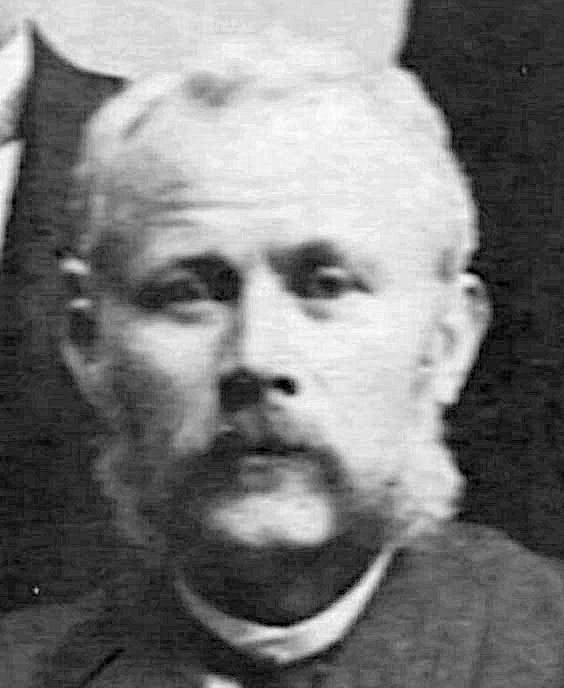

Our starting–point is Nils Kristian♂ (b. 1843 d. 1921), the son of Jens Christian Pedersen♂ (son of Peder) and Johanne Nielsdatter♀ (daughter of Niels ;)

As was common he was given the name from his father “Nils, son of  Jens”, or “Jensen”. The second “s” popped up later in church and state documents. Getting names right depended highly on how bad the priest’s hearing were when you went to register the child for baptism …1

Jens”, or “Jensen”. The second “s” popped up later in church and state documents. Getting names right depended highly on how bad the priest’s hearing were when you went to register the child for baptism …1

And here we start our story; from this generation on the surname is inherited on the spear side — patrilineal inheritance. It is also the moment that Moss comes into play; both of Nils Kristian’s parents lived close to the Swedish border, away from the coast.

Nils Kristian grew up, found love, and in 1867 he married Jørgine Olava Larsdatter (b. 1846 d. 1908) and sought employment — and  accommodation — at the local iron works. Factories at the time had, quite often, reasonably cheap, if also of unreasonably poor standard, housing2 for their employees and families. Some of the buildings are standing to this day, although no kid need grow up in one.

accommodation — at the local iron works. Factories at the time had, quite often, reasonably cheap, if also of unreasonably poor standard, housing2 for their employees and families. Some of the buildings are standing to this day, although no kid need grow up in one.

There’s not much more to say on the topic of Nils Kristian, except that he and his wife moved late in life, to Sannidal in Kragerø on the south coast; she died there in 1908, after which he married Anna Hoaas♀ in 1911. She brought two daughters from a previous marriage; there were no further children.

Jørgine Olava had busy days during their life in Moss, and by the time of the move an entire football team worth of children had seen the light: Johan Laurits♂ (b. 1866 d. 1917), Carl Edvard♂ (b. 1869 d. 1923), Wilhelm♂ (b. 1870 d. 1953), Nils Christian♂ (b. 1872 d. ?), Johanne♀ (b. 1874 d. 1948), Jens♂ (b. 1876 d. 1921), Marie♀ (b. 1879 d. ?), Lovise♀ (b. 1884 d. 1968), Gustav Kornelius♂ (b. 1885 d. 1968), and Sigrid♀ (b. 1887 d. ?).

Johanne moved to Oslo, presumably, as we can find her in a church record from Uranienborg (which is in Oslo, hence the presumption … ) in 1897 when she married Emil Sagerström of Årjäng (Sweden). They moved from Norway in 1888; by 1910 they live in Älvsborg with seven children.

Lovise did much the same — she married Abraham Elias Jonsen (b. 1884 d. 1981) in Oslo the 25th of September 1910. By 1920 we find them in Sannidal. Not a stretch to connect that move with mum and dad, what?

Marie I find nothing about, save that she was confirmed in 1894.

Two of their brothers made a splash, each in their own way. The second oldest, Carl Edvard, made his living as a machinist, and was elected to Stortinget (the Parliament) for Moss Arbeiderparti (the Labour Party) between 1913 and 1915. He was also on the city council between 1907 and 1922. As a reward they named a rather short stump of road, a few hundred meters long, after him. It runs between Melløs and Verlebukta in Moss.

In 1895 he married Ingeborg Kristine Blondin♀ (b. 1872, no relation to Charles3 d. 1935); in 1899 his brother Jens married her sister Karoline Margrette♀ (b. 1879 d. 1914). One might suspect the Jenssen boys of making a habit of it, but luckily Johan Laurits ties the knot with Albertine Sofie Svendsen♀ (b. 1869 d. 1942) in 1894.

Nils Christian “Jr.” does the deed with Katinka Larsen♀ (b. 1877 d. ?) in 1902, and Wilhelm marries Anna Kristine Knudsen♀ (b. 1874 d. 1936) at some point in time …

But it is Johan Laurits who is our focus now. He goes to sea, and in 1917 was second engineer on S/S Baltique when the ship docks in England. The first world war is in full flow, and he goes ashore to temporarily lodge with Mrs. Watson, at number 9 Bede Street, South Shields.

Here the tale turns dark. On the 9th of February 1918 his wife Albertine receives a letter from chaplain Niels Steen of the Norwegian Sea men’s Church (Sjømannskirken) in England: Johan has died of pneumonia; without much ceremony, but under a wrong name, he was buried at Harton Cemetery in December 1917. He leaves five pounds; much more than that one could perhaps not expect a sailor to save at the time. It’s a couple of thousand Norwegian Kroner; a not insubstantial sum of money in the day and age.

That letter is in my archive too.

In Norway Albertine was left with Gerda♀ (b. 1889 d. 1942), Nils Kristian♂ (b. 1894 d. 1970), Sigrid♀ (b. 1896 d. 1987), Ellen♀ (b. 1897 d. 1900), Reinhart♂ (b. 1899 d. 1943), Jørgen♂ (f. 1902 d. 1933) and Albert♂ (b. 1902 d. 1902), Gerhard♂ (b. 1904 d. 1975), Otter♂ (b. 1906 d. 1907) and little Karl♂ (b. 1909 d. 1980).

There’s quite a bit more movement to this generation! Karl moves to Tynset and takes up farm work; Sigrid becomes a housewife in Brooklyn, Gerda runs a household in Telemark, Jørgen sets up family on Iceland. Nils Kristian “Jr.” is an able seaman in the merchant marine during World War Two, and Reinhart worked the lonely work of a stoker until sunk by U–86 at grid AK 9793 on board D/S Brant County the 11th of March 1943 4…

Ellen Solveig Dina dies young, at a mere three years of age, Otter lived a year, and Jørgen’s twin Albert made it to sixteen days and no more. Overall a sad story.

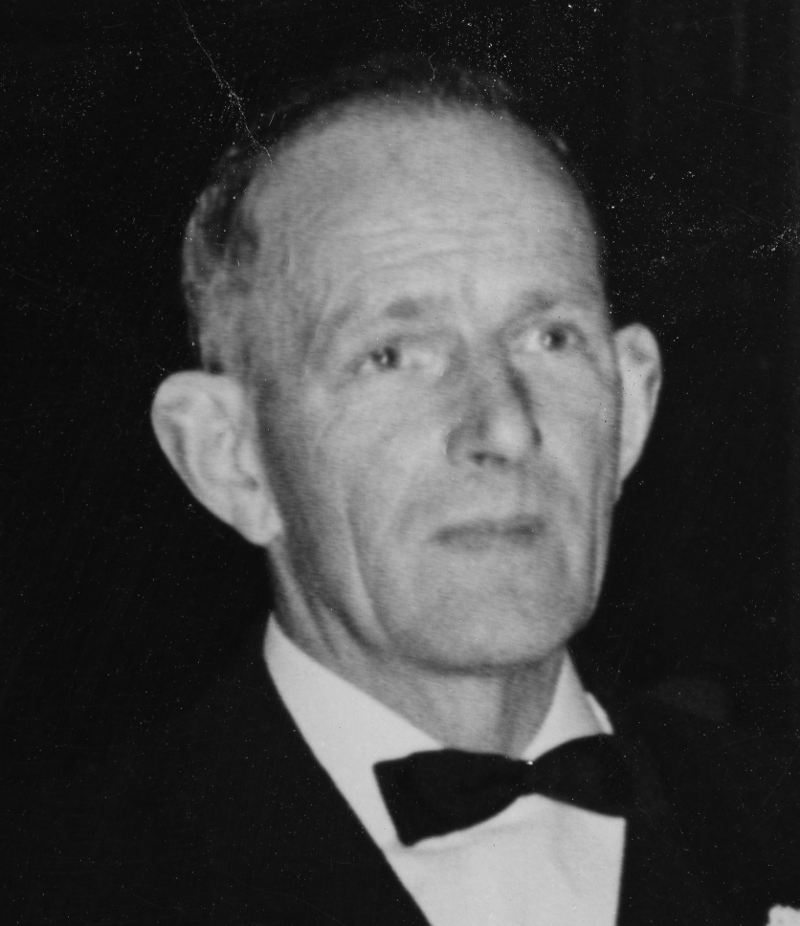

Tormod Gerhard remains in Moss, and lands a position at Moss Verft & Dokk (the local before–mentioned shipyard) straight out of school; this was 1918 and the boy had turned 14. A year later he joins the Norwegian Union of Iron and Metalworkers and the next fifty years see him work on increasingly larger ships, marrying Elvine Johansen♀ (b. 1898, Oslo, d. 1985 ), build a house with his own two hands and raised a family of three: Thorleif Emil♂ (b. 1932), Åge Gerhard♂ (b. 1934) and Aslaug Ellen♀ (b. 1938 d. 1999).

Carrying a diploma celebrating 50 years in the Union, Gerhard retired in 1969. It didn’t last. As a hobby he had spent his free time repairing the various technical gadget of the school next door, and until 1974 he officially holds the position of janitor5.

It took five heart attacks to finally do for grandfather Gerhard in 1975. His wife Elvine lived on in their house at Hasselbakken until her death ten years later.

Thorleif followed his father and ended up a foreman at the shipyard, built his house on a rock–filled piece of land at Rosnes, spent his winters fishing, his summers rowing (double scull), and all the year shooting competitive archery. He married Øyvor Grøneng♀ (b. 1935 d. 2021) and had a son.

Åge turned his hand to engineering at Chalmers in Sweden, and worked the rest of his career for the Norwegian State Railways. He never moved out, but lived at home with his wife Elsa Jacobsen♀ (b. 1935) and mother Elvine.

Aslaug — mum — went to business school, moved to Oslo in 1956 and  worked on IBM mainframes long before computers became commonplace. The official title was “secretary”; the work was varied to say the least. Today she’d be called a PA and receive rather more recognition (and cash!)

worked on IBM mainframes long before computers became commonplace. The official title was “secretary”; the work was varied to say the least. Today she’d be called a PA and receive rather more recognition (and cash!)

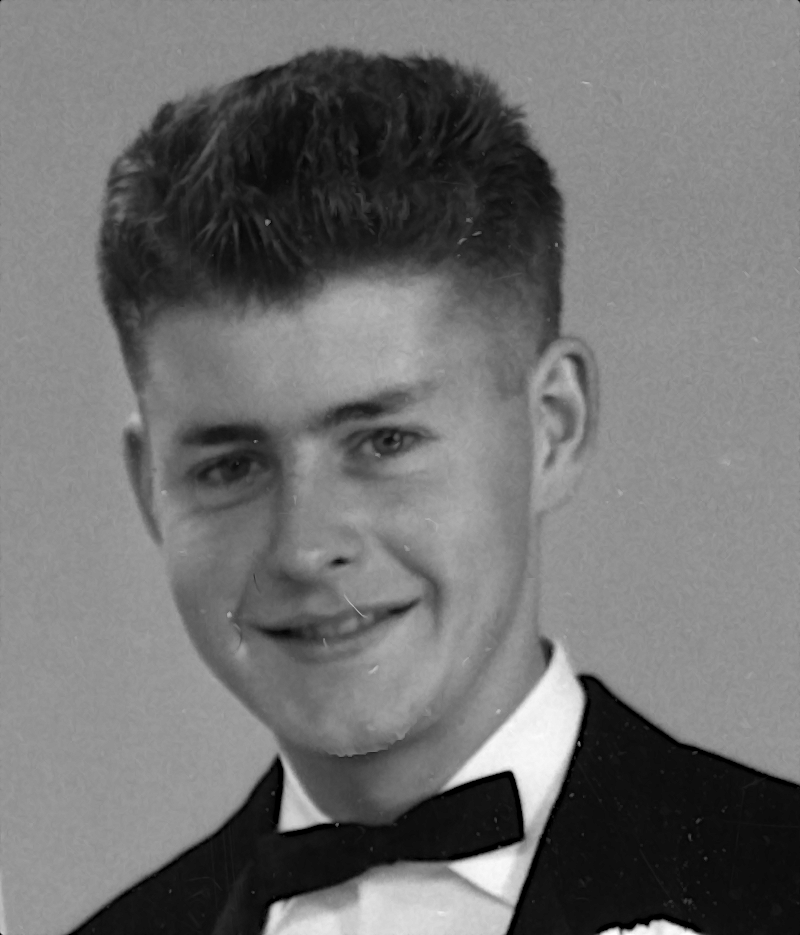

She met and married her husband Jan in 1960; I toodled along in ’68. Dad died in 1973, and we moved back to Moss. Mum was a true product of her parents — stubborn, efficient, kind, and intelligent. I have many fond memories of her. She died in 1999.

Mum and dad are both buried in the family urn grave in Moss, alongside my grandfather, grandmother and uncle. This particular branch of the Jenssen family ends with my cousin and me, as neither of us have — nor will have — kids of our own.

Dad — Jan Eigil Holmboe (b. 1936 d. 1973) — was born to mother Ruth Olsen but not, as it transpires, to father Halvar Holmboe. Hence it get a bit tricky.

I have, all my life, known that dad was adopted into the Holmboe family. With some regret I can say that I never cared, partially because he died when I was four, and partially ’cause, well, he was dad, wasn’t he? At that age the event horizon is a touch limited. Mine never evolved much …

His adopted father — and biological mother — was in the picture, but I remember neither of them. He had a sister, whom I guess I did meet at some time … it’s rather a blur.

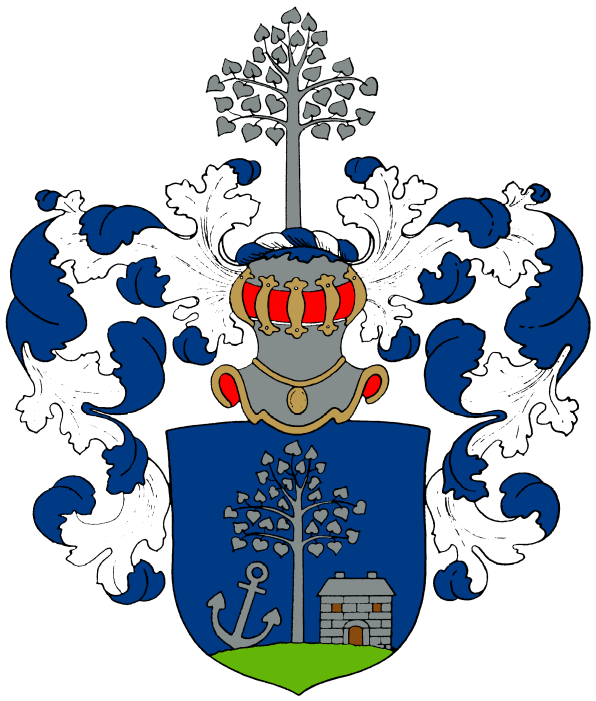

So, we go back two steps. The Holmboe family is a tad snooty (eh, what?) and sport not only a coat of arms but a wikipedia entry of their own. Good as royalty these days :)

This brings us back to the first flashback: the name is solidly protected by law in Norway.

Originally from Denmark, the Norwegian branch springs from brothers Jens Olsøn Holmboe (b. 1671 d. 1743) and Hans Olsøn Holmboe (b. 1685 d. 1762) who upped and moved country6  some time between 1705 and 1715.

some time between 1705 and 1715.

By fits and starts7 the branch coughed out Georg Rudolf Holmboe (b. 1880) who, in turn, had son Halvar (b. 1918).

Halvar and Ruth married in 1943, when Jan — dad — was seven years old. In 1960 he was, officially, adopted by Halvar. There’s a discrepancy here which is somewhat difficult to understand: in my archive I have this enrolment papers in the Norwegian Armed Forces anno 1954 … as Jan Eigil Holmboe. See above for the protected by law bit.

Be that as it may. The official adoption date was the 31st of August 1960, less than two months before he married mum. None of the participants are alive today to explain. Mea culpa8.

There’s little in the way of memories when it comes to dad. He worked, for many years, in the publishing business — mostly in the area of  moving books from one place to another in a warehouse. Not long before his death he was promoted to a management position. We all suspect the stress and a more sedentary lifestyle was the reason.

moving books from one place to another in a warehouse. Not long before his death he was promoted to a management position. We all suspect the stress and a more sedentary lifestyle was the reason.

I do have some — fond — memories of that warehouse filled with books though, and getting to drive a forklift.

Knowing about the adoption, and having a vague memory of the name Rinker, I finally set out to dig in the official papers. Luckily there’s a law back home in Norway which state that the child of an adoptee have the right to learn the name of their biological grandfather.

Bureaucracy ensued.

In January 2023 the name Aksel Øivind Rinker (b. 1910 d. 1962) appeared from the dusty depths of a government archive.

It made sense. He and Ruth lived pretty exactly 10 kilometres, if eight years, apart. It’s even likely they were born in the same place; the first census records I find of them are more–or–less equidistant from the district hospital.

We can but imagine how they met, but they did so in the summer of 1935 and — it is not too great a leap of imagination — had (at least once) carnal relations. In March of ’36 dad was born.

We can but imagine how they met, but they did so in the summer of 1935 and — it is not too great a leap of imagination — had (at least once) carnal relations. In March of ’36 dad was born.

After this it gets more difficult. I can find no trace9 of the slippery fellow between 1935 and 1938. In February of the latter he goes to sea on the M/T Pericles and, for the next 13 years, works his way back and forth across the Atlantic ocean from “assistant to the 3rd engineer” to “Chief Engineer”. Nothing worth mentioning, really, except that he touched down in Norway in ’46 and got himself engaged to Tordis Dybesland.

At the tender age of 46 he turns in his Norwegian citizenship for a US one, marries Astrid (possible surname Lassen or Larsen) – not the person he got engaged to above, four years earlier, nor the woman he had a son with ten years earlier — and settles in working for Gulf Oil … until his death in 1962.

They are both buried in Brooklyn’s Green–Wood cemetery, not too many streets from where my mum’s paternal aunt took up residency in 1972. Thus endeth the story of my biological grandfather. As far as I know he had no other children.

Let’s go back in time, to 1853. This is the year a healthy young chap named Johan Marthinius Rinker was born to Marthe Olivia Asbjørnsen (b. 1822 d. 1905) and Johannes Rinker (b. 1822 d. 1884) … and this is where it gets interesting indeed. For while every other person in my family is as common as muck, this fellow moved to Norway from Prussia around 1847.

The eighteen hundreds were not a time you moved willy–nilly when the mood took you, but it was a period where emerging industry required experts in metal–working. Johannes made molds and, a wild guess here, he worked with cast iron.

A happy coincidence led me to the personal website of a relative–I–never–knew–about, and hence to a number of newspaper articles on the foundry Drammens Jernstøberi to which, the journalist was quite happy to report, the owner (one Blichfeldt) imported German know–how … including an expert in molding, Rincher. This was in 1846.

In 1850 he married Marthe Olivia Asbjørnsdatter (b. 1822 d. 1905); together they had children Johan Marthinius (b. 1853 d. 1925), Anna Marie (b. 1851 d. 1892), Carl Fredrich (b. 1860) and Oscar August (b. 1866 d. 1867).

His grandson, Gustav Karl, followed in his grandfather’s footsteps, if one is to believe a newspaper clipping I found. Here he poses with granddads tools, still in use …

Borders, as you may be aware, are just a little bit different in Europe anno 2023 than they were in 1822, so it took some digging: Johannes Rinker was very likely born to Philipp Rinker (b. 1795 d. 1875) and Klara Emrich (b. 1797 d. 1863) in Aßlar, Lahn–Dill–Kreis, Hessen (currently Germany)10.

From there it rather launched itself, to be honest, if backwards, culminating in one Jacob Klein (b. 1580) of which I know absolutely nothing else.

Curious to note: there’s a veritable sea of descendants from Herr Klein.

There exist an article — I know, I wrote it — on the topic of the Rinker family. At the point of writing, it is in Norwegian. If I have the time I might rewrite.

This is a non–exhaustive list of the sources used for the research and article, not sorted on either trustworthiness or date.

1 Somewhat amusingly, you can tell when a new priest started work in a parish from the old church records. Not necessarily when the handwriting changed, but when it suddenly becomes legible and moving horizontally across the page …

2 “I owe my soul to the company store … ”

3 Charles Blondin? The Great Blondin? Honestly. What do they feed kids these days…. Look’im up!

4 See https://www.warsailors.com and https://www.krigsseilerregisteret.no

5 Let’s be honest: he was more a building engineer, maintaining and repairing fairly complex technical equipment. The school was designed for students with various degrees of physical impediments, and some of the mechanics was difficult. But Norway has always — if not as badly as Sweden — been a touch elitist. Doing the job of an engineer doesn’t mean you get to call yourself one, or get paid as one. Granddad didn’t care. He just loved tinkering.

6 Well … they didn’t actually move between one country and another. Between 1380 and 1814 Norway and Denmark was in various forms of union.

7 There exist an Official Family Record (insert eyes rolling furiously here) based on a legacy from bailiff Jens Holmboe (d. 1804 – and got a bauta!) which, in an edition ca. 1944, claimed that Rudolf had appropriated the name incorrectly. This has later been changed.

8 For not asking while I had the time. The other bit is not my fault!

9 Government records. Church records. Myheritage. Familysearch. Ancestry. The tooth fairy! You name it, I didn’t find it there.

10 Per January 2023, a large part of the information on the Rinkers of Prussia is gleaned from various family trees at Ancestry. The information has not been double–checked for correctness.

index

2009 — 2013 archive (aka "ye olde stuff")

© Tina Holmboe, Jörgen Andreasen

2010 — 2023

Creative Commons BY-ND 4.0